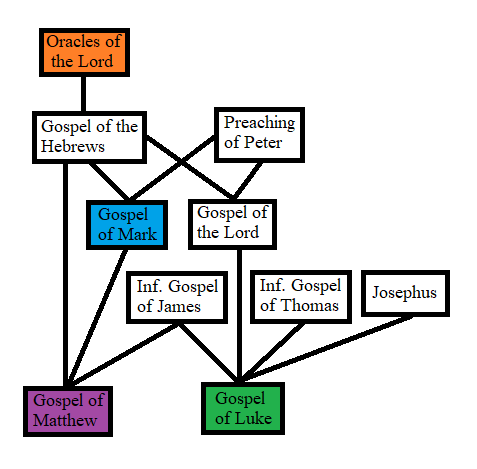

Here is a brief introduction to my solution to the synoptic problem:

According to Papias (an early second-century follower of John), the Oracles of the Lord (sayings of Jesus) were written down by Matthew in Hebrew/Aramaic script. This is either the Gospel of Thomas or something closely resembling the Gospel of Thomas (the half of Thomas with parallel attestations in Matthew or Luke). The apostles then interpreted these oracles as they were able, which I take to mean they collaboratively recalled the events surrounding each of the sayings and joined these narratives together chronologically into the Gospel of the Hebrews, adding additional material and sayings of Jesus that were recalled throughout this exercise of collaborative recollection. One such instance of this would have to be the transfiguration and other events that would not have been witnessed by Matthew (or Judas Thomas), but would have been attested to by multiple witnesses present (John, James, and Peter). The Oracles of the Lord and the Gospel of the Hebrews would have been composed in apostolic times, likely soon after the departure of Jesus, before each apostle left on their separate missionary trips throughout different parts of the world, and while the memories were all still fresh in their minds. I would thus date both texts to the early-to-mid-30s.

Papias describes Mark as an interpreter of Peter. Historically, this has been commonly understood to mean Mark was a disciple following Peter around and translating his sermons (from Hebrew/Aramaic to Greek, I suppose?). Given that Papias’ use of ‘interpret‘ in reference to the oracles means ‘construct a sequential narrative from fragmentary source material’, I think the more internally consistent understanding of Papias is that Mark was trying to construct a sequential narrative from the fragmentary source material found in what is later attested to as ‘the Preachings of Peter‘ text. Unlike the apostles, who could attest firsthand to the chronology of events interpreted from the oracles, Mark was not a disciple who knew Jesus or who witnessed any of the events firsthand. He therefore could not affirm the correct ordering of events, but according to Papias, he nevertheless took great care not to add or distort anything to the material he was copying down from his sources.

The Preaching of Peter, based on early references, fragments, and quotations, likely existed in the mid-to-late first century. What is known today as the Gospel of Peter fragment containing a passion and resurrection narrative shows multiple indications of being part of this same collection of texts attributed to the Apostle Peter. The author of this Preaching of Peter material was believed by many to be the Apostle Peter, including evidently the authors of the Gospel of Mark and the Gospel of the Lord, as well as several of the commenters referencing the text in later centuries. It is worth mentioning, however, that an equally ancient tradition dating back to the apostolic era attests to the spurious nature of this text, identifying the pseudo-Petrine authorship as Simon Magus and his followers.

According to this tradition, the purpose of the Preaching of Peter text was to distort Peter’s character and teachings so as to lead people astray from knowing and following the Lord. This concurrent Petrine tradition rejected the Preaching of Peter text, as well as the texts that were (at least partially) derived from it, including the Gospel of Mark, the Gospel of the Lord, the Gospel of Luke, and the Gospel of Matthew. They used only the original Gospel of the Hebrews, even up through the fourth century. This alternate tradition is attested to in some early Jewish Christian sources partially preserved within Ebionite and Nazarene texts, most notably the Clementine Homilies and Recognitions of Clement. Heresiologies (by Iranaeus, Epiphanius, and others) attest to the beliefs of these early Jewish Christians, as well as their rejection of all the gospels other than the Gospel of the Hebrews.

The Gospel of the Lord is not attested to by Papias. Our earliest witness of it is its use by Marcion of Sinope somewhere between 120 and 160. Its authorship is traditionally ascribed to Luke, a travel companion of Paul, but the earliest attestation of Lukan authorship is in the late second century (180-185) by Iranaeus in Against Heresies. Whoever authored it, they evidently used the same two sources as Mark (the Gospel of the Hebrews and the Preaching of Peter) and were thus likely writing around the same time period as Mark. Based on my literary analysis of the respective texts, I see no evidence of dependency between the Gospel of Mark and the Gospel of the Lord. They appear to have been using the same two sources completely independently of each other.

What has come to be known as the canonical Gospel of Luke uses the Gospel of the Lord as its primary source, although according to the attestations we have of the Gospel of the Lord (by Tertullian and Epiphanius), the arrangement of its material differs somewhat from that found in the canonical Gospel of Luke. The canonical Gospel of Luke also used the Protoevangelium (Infancy Gospel) of James and the Infancy Gospel of Thomas for the material comprising its first two chapters. There is also evidence that this author used material from Josephus to fill in historical details not found in the Gospel of the Lord. The canonical Gospel of Luke was addressed to Theophilus, who was bishop of Antioch from 168 to 182. The Book of Acts was written shortly thereafter by the same author and likewise addressed to Theophilus. I would thus date the canonical Gospel of Luke to 168-170 and the Book of Acts to 170-175. The canonical Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts are, by their own internal attestations (in the opening prologue in Luke 1 and Acts 1), primarily composite documents of earlier source material joined together for the instruction of Theophilus.

Like the canonical Gospel of Luke, the canonical Gospel of Matthew used the Protoevangelium (Infancy Gospel) of James for the infancy narrative that comprises its first two chapters. The rest of its material derives from the Gospel of Mark and the Gospel of the Hebrews (albeit likely a Greek translation of the Gospel of the Hebrews that includes a mistranslation of enkris/akris repeated by Justin concerning John’s food). The Gospel of Mark and the Gospel of the Lord were likely composed in the late first century or early second century, around the same time as each other. The canonical Gospel of Luke and canonical Gospel of Matthew were likewise composed around the same time as each other. Justin, who was writing between 150 and 160, shows reliance on the Protoevangelium (Infancy Gospel) of James for his birth narrative material (Jesus being born in a cave), indicating that his Mathew-Luke material is probably derived from an earlier source, most likely a Greek translation of the Gospel of the Hebrews, possibly with the Protoevangelium (Infancy Gospel) of James attached to the beginning, that he calls ‘the memoirs of the apostles‘. This also explains why his quotations do not line up exactly with the canonical texts, since he is using their source text rather than the texts themselves that were composed later. The canonical Gospels of Matthew and Luke would thus have to be composed after Justin (160) and before Iranaeus (185). I therefore date both to around 170.

After the canonical Gospel of Mathew was composed, the Gospel of the Hebrews was often thereafter referred to as the Hebrew Gospel of Matthew. Sorting out the variety of attestations to the Gospel of the Hebrews is a separate complex endeavor with no direct bearing on my synoptic model, but it is relevant for making sense of all the various overlapping and often confused attestations of related texts. My current best understanding is that versions of the Gospel of the Hebrews with the Protoevangelium (Infancy Gospel) of James attached to the beginning are referred to as the Gospel of the Nazarenes or the (complete) Hebrew (or Judaic) Gospel of Matthew. Versions of the Gospel of the Hebrews without the Protoevangelium (Infancy Gospel) of James attached to the beginning are often attested to as the Gospel of the Ebionites.

Leave a comment